Košice

Košice | |

|---|---|

Top: Cathedral of St. Elizabeth and St Michael Chapel Center: general aerial view Bottom (left to right): State Theater; Center of Hlavná street; Coat of Arms Statue Superimposed: coat of arms | |

| Nickname: City of Tolerance[1] | |

| Coordinates: 48°43′N 21°15′E / 48.717°N 21.250°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Košice Self-governing Region |

| District | Košice I, Košice II, Košice III, Košice IV |

| First mentioned | 1230 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jaroslav Polaček |

| Area | |

• City | 243.7 km2 (94.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 206 m (676 ft) |

| Population (2024-01-01[2]) | |

• City | 225,044 |

| • Density | 920/km2 (2,400/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 368,725 |

| Demonym(s) | Košičan (m.) Košičanka (f.) (sk) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 040 00 |

| Area code | +421-55 |

| GDP | 2017 |

| – Total | Nominal: €18 billion PPP: $21 billion |

| – Per capita | Nominal:

€18,100 PPP: $16,300 |

| Website | https://www.kosice.sk |

Košice (UK: /ˈkɒʃɪtsə/ KOSH-it-sə,[3] Slovak: [ˈkɔʂitse] ⓘ; Hungarian: Kassa [ˈkɒʃʃɒ] ⓘ)[a] is the largest city in eastern Slovakia. It is situated on the river Hornád at the eastern reaches of the Slovak Ore Mountains, near the border with Hungary. With a population of approximately 230,000, Košice is the second-largest city in Slovakia, after the capital Bratislava.

Being the economic and cultural centre of eastern Slovakia, Košice is the seat of the Košice Region and Košice Self-governing Region, and is home to the Slovak Constitutional Court, three universities, various dioceses, and many museums, galleries, and theatres. In 2013 Košice was the European Capital of Culture, together with Marseille, France. Košice is an important industrial centre of Slovakia, and the U.S. Steel Košice steel mill is the largest employer in the city. The town has extensive railway connections and an international airport.

The city has a preserved historical centre which is the largest among Slovak towns. There are heritage protected buildings in Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and Art Nouveau styles with Slovakia's largest church: the Cathedral of St. Elizabeth. The long main street, rimmed with aristocratic palaces, Catholic churches, and townsfolk's houses, is a thriving pedestrian zone with boutiques, cafés, and restaurants. The city is known as the first settlement in Europe to be granted its own coat-of-arms.[4]

Etymology

[edit]The first written mention of the city was in 1230 as "Villa Cassa".[5] The name probably comes from the Slavic personal name Koš, Koša → Košici (Koš'people) → Košice (1382–1383) with the patronymic Slavic suffix "-ice" through a natural development in Slovak (similar place names are also known from other Slavic countries).[6][7] In Hungarian Koša → Kasa, Kassa with a vowel mutation typical for the borrowing of old Slavic names in the region (Vojkovce → Vajkócz, Sokoľ → Szakalya, Szakál, Hodkovce → Hatkóc, etc.).[8] The Latinized form Cassovia became common in the 15th century.[7]

Another theory is a derivation from Old Slovak kosa, "clearing", related to modern Slovak kosiť, "to reap".[9] According to other sources the city name may derive from an old Hungarian[10] first name which begins with "Ko".[11]

Historically, the city has been known as Kaschau in German, Kassa in Hungarian, Kaşa in Turkish, Cassovia in Latin, Cassovie in French, Cașovia in Romanian, Кошице (Košice) in Russian, Ukrainian and Rusyn, Koszyce in Polish and קאשוי Kashoy in Yiddish (see here for more names). Below is a chronology of the various names:[12][13][14][15]

| Year | Name | Year | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1230 | Villa Cassa | 1420 | Caschowia |

| 1257 | Cassa | 1441 | Cassovia, Kassa, Kaschau, Košice |

| 1261 | Cassa, Cassa-Superior | 1613–1684 | Cassovia, Kassa, Kaşa, Kossicze |

| 1282 | Kossa | 1773 | Cassovia, Kassa, Kaschau, Kossicze |

| 1300 | Cossa | 1786 | Cassovia, Kascha, Kaschau, Kossice |

| 1307 | Cascha | 1808 | Cassovia, Kaschau, Kassa, Kossice |

| 1324 | Casschaw | 1863–1913 | Kassa |

| 1342 | Kassa | 1918–1938 | Košice |

| 1388 | Cassa-Cassouia | 1938–1945 | Kassa |

| 1394 | Cassow | 1945– | Košice |

History

[edit]

Kingdom of Hungary 1000 – 1526

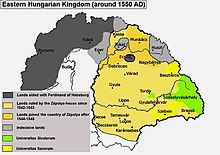

John Zápolya's Eastern Hungarian Kingdom 1526 – 1551 (Ottoman vassal)

Hajduk rebels of István Bocskai 1604 – 1606 (Ottoman-backed)

Principality of Transylvania (Ottoman vassal) 1619 – 1629, 1644 – 1648

Kuruc rebellion 1672 – 1682 (Ottoman-backed)

Imre Thököly's Principality of Upper Hungary (Ottoman vassal) 1682 – 1686

Francis II Rákóczi's insurrection 1703 – 1711

Kingdom of Hungary (crownland of the Austrian Empire) 1804 – 1867

Austro-Hungarian Empire 1867 – 1918

Czechoslovakia 1918–1938

First Slovak Republic 1938 – 1945

Czechoslovakia 1945–1992

Slovakia 1993–present

The first evidence of habitation can be traced back to the end of the Paleolithic era. The first written reference to the Hungarian town of Košice (as the royal village of Villa Cassa) comes from 1230. After the Mongol invasion in 1241, King Béla IV of Hungary invited German colonists (see Zipser Germans, Germans of Hungary) to fill the gaps in population. The city was in the historic Abauj County of the Kingdom of Hungary.

There were two independent settlements, Lower Kassa and Upper Kassa, which were amalgamated in the 13th century around the long lens-shaped ring, of today's Main Street. The first known town privileges come from 1290.[16] The town proliferated because of its strategic location on an international trade route from agriculturally rich central Hungary to central Poland, itself part of a longer route connecting the Balkans and the Adriatic and Aegean seas to the Baltic Sea. The privileges given by the king were helpful in developing crafts, business, increasing importance (seat of the royal chamber[clarification needed] for Upper Hungary), and for building its strong fortifications.[5] In 1307, the first guild regulations were registered here; they were the oldest in the Kingdom of Hungary.[17]

As a Hungarian free royal town, Košice reinforced the king's troops at the crucial moment of the bloody Battle of Rozgony in 1312 against the strong aristocratic Palatine Amadé Aba (family).[18][19] In 1347, it became the second-placed city in the hierarchy of the Hungarian free royal towns, with the same rights as the capital Buda. In 1369, it was granted its own coat of arms by Louis I of Hungary.[16] The Diet convened by Louis I in Košice decided that women could inherit the Hungarian throne.

The significance and wealth of the city at the end of the 14th century were mirrored by the decision to build an entirely new church on the grounds of the previously destroyed smaller St. Elisabeth Church. The construction of St. Elisabeth Cathedral, the biggest cathedral in the Kingdom of Hungary, was supported by Emperor Sigismund, and by the apostolic see itself. From the beginning of the 15th century, the city played a leading role in the Pentapolitana – the league of the five most important cities in Upper Hungary (Bardejov, Levoča, Košice, Prešov, and Sabinov). During the reign of King Matthias Corvinus the town reached its medieval population peak. With an estimated 10,000 inhabitants, it was among the largest medieval cities in Europe.[21]

The history of Košice was heavily influenced by the dynastic disputes over the Hungarian throne which, together with the decline of the continental trade, brought the city into stagnation. Vladislaus III of Varna failed to capture the city in 1441. John Jiskra's mercenaries from Bohemia defeated Tamás Székely's Hungarian army in 1449. John I Albert, Prince of Poland, failed to capture the city during a six-month-long siege in 1491. In 1526, the city paid homage to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I. John Zápolya captured the town in 1536, but Ferdinand I reconquered it in 1551.[22] In 1554, the settlement became the seat of the Captaincy of Upper Hungary.

17th century

[edit]In 1604, Catholics seized the Lutheran church in Košice.[23] The Calvinist Stephen Bocskay then occupied Košice during his Protestant insurrection against the Habsburg dynasty, with the backing of the Ottomans. The future George I Rákóczi joined him as a military commander there. Giorgio Basta, commander of the Habsburg forces, failed in his attempt to recapture the city. At the Treaty of Vienna (1606), in return for giving back territory that included Košice, the rebels won from the Habsburgs a concession of religious toleration for the Magyar nobility and brokered an Austrian-Turkish peace treaty. Stephen Bocskay died in Košice on December 29, 1606, and was interred there.

For some decades during the 17th century Košice was part of the Principality of Transylvania, and consequently a part of the Ottoman Empire and was referred to as Kaşa in Turkish.[15] On September 5, 1619, the prince of Transylvania, Gabriel Bethlen captured Košice with the assistance of the future George I Rákóczi in another anti-Habsburg insurrection. By the Peace of Nikolsburg in 1621, the Habsburgs restored the religious toleration agreement of 1606 and recognized Transylvanian rule over the seven Partium counties: Ugocsa County, Bereg County, Zemplén County, Borsod County, Szabolcs County, Szatmár County and Abaúj County (including Košice).[24] Bethlen married Catherine von Hohenzollern, of Johann Sigismund Kurfürst von Brandenburg, in Košice in 1626.[25]

After Bethlen's death in 1629, Košice and the rest of the Partium was returned to the Habsburgs.[24]

On January 18, 1644, the Diet in Košice elected George I Rákóczi the prince of Hungary. He took the whole of Upper Hungary and joined the Swedish army besieging Brno for a projected march against Vienna. However, his nominal overlord, the Ottoman Sultan, ordered him to end the campaign, though he did so with gains. In the Treaty of Linz (1645), Košice returned to Transylvania again as the Habsburgs recognized George's rule over the seven counties of the Partium.[24] He died in 1648, and Košice was returned to the Habsburgs once more.[26]

Subsequently, Košice became a centre of the Counter-Reformation. In 1657, a printing house and university were founded by the Jesuits, funded by Emperor Leopold I. The 1664 Peace of Vasvár at the end of the Austro-Turkish War (1663-1664) awarded Szabolcs and Szatmár counties to the Habsburgs,[27] which put once more positioned Košice further inside the borders of Royal Hungary. In the 1670s the Habsburgs built a modern pentagonal fortress (citadel) south of the city. Also in the 1670s, the city was besieged by Kuruc armies several times, and it again rebelled against the Habsburgs. The rebel leaders were massacred by the Emperor's soldiers on November 26, 1677.

Another rebel leader, Imre Thököly captured the city in 1682, making Kaşa once again a vassal territory of the Ottoman Empire under the Principality of Upper Hungary until 1686. The Austrian field marshal Aeneas de Caprara took Košice back from the Ottomans in late 1685. In 1704–1711 Prince of Transylvania Francis II Rákóczi made Košice the main base in his War for Independence. By 1713 the fortress had been demolished.

When not under Ottoman suzerainty, Košice was the seat of the Habsburg "Captaincy of Upper Hungary" and the seat of the Chamber of Szepes County (Spiš, Zips), which was a subsidiary of the supreme financial agency in Vienna responsible for Upper Hungary. Due to Ottoman occupation of Eger, Košice was the residence of Eger's archbishop from 1596 to 1700.[28]

From 1657, it was the seat of the historic Royal University of Kassa (Universitas Cassoviensis), founded by Bishop Benedict Kishdy. The university was transformed into a Royal Academy in 1777, then into a Law Academy in the 19th century. It was to cease to exist in the turbulent year 1921. After the end of the anti-Habsburg uprisings in 1711, the victorious Austrian armies drove the Ottoman Army back to the south, and this major territorial change created new trade routes which circumvented Košice. The city began to decline and from a rich medieval town became a provincial town known for its military base and mainly dependent on agriculture.[29]

In 1723, the Immaculata statue was erected on the site of a former gallows at Hlavná ulica (Main Street) to commemorate the plague of 1710–1711.[30] The city also became one of the centers of the Hungarian linguistic revival, including the publication of the first Hungarian-language periodical, called the Magyar Museum, in Hungary in 1788.[31] The city's walls were demolished step by step from the early 19th century to 1856; only the Executioner's Bastion remained among limited parts of the wall. The city became the seat of its own bishopric in 1802. The city's surroundings became a theater of war again during the Revolutions of 1848, when the Imperial cavalry general Franz Schlik defeated the Hungarian army on December 8, 1848, and January 4, 1849. The city was captured by the Hungarian army on February 15, 1849, but the Russian troops drove them back on June 24, 1849.[32]

In 1828, there were three manufacturers and 460 workshops.[33] The first factories were established in the 1840s (sugar and nail factories). The first telegram message arrived in 1856, and the railway connected the city to Miskolc in 1860. In 1873, there were already connections to Prešov, Žilina, and Chop, Ukraine (in today's Ukraine). The city gained a public transit system in 1891 when the track was laid down for a horse-drawn tramway. The traction was electrified in 1914.[33] In 1906, Francis II Rákóczi's house of Rodostó was reproduced in Košice, and his remains were buried in the St. Elisabeth Cathedral.[34]

After World War I and during the gradual break-up of Austria-Hungary, the city at first became a part of the transient "Eastern Slovak Republic", declared on December 11, 1918, in Košice and earlier in Prešov under the protection of Hungary. On December 29, 1918, the Czechoslovak Legions entered the city, making it part of the newly established Czechoslovakia. However, in June 1919, Košice was occupied again, as part of the Slovak Soviet Republic, a proletarian puppet state of Hungary. The Czechoslovak troops secured the city for Czechoslovakia in July 1919,[35] which was later upheld under the terms of the Treaty of Trianon in 1920.

Fate of Košice Jews

[edit]Jews had lived in Košice since the 16th century but were not allowed to settle permanently. There is a document identifying the local coiner in 1524 as a Jew and claiming that his predecessor was a Jew as well. Jews were allowed to enter the city during the town fair, but were forced to leave it by night, and lived mostly in nearby Rozunfaca. In 1840 the ban was removed, and, a few Jews were living in the town, among them a widow who ran a small Kosher restaurant for the Jewish merchants passing through the town.

Košice was ceded to Hungary, by the First Vienna Award, from 1938 until early 1945. The town was bombarded on June 26, 1941, by a still unidentified aircraft,[36] in what became a pretext for the Hungarian government to declare war on the Soviet Union a day later.

The German occupation of Hungary led to the deportation of Košice's entire Jewish population of 12,000 and an additional 2,000 from surrounding areas via cattle cars to the concentration camps.

In 1946, after the war, Košice was the site of an orthodox festival, with a Mizrachi convention and a Bnei Akiva Yeshiva (school) for Jews, which, later that year, moved with its students to Israel.[37]

A memorial plaque in honor to the 12,000 deported Jews from Košice and the surrounding areas in Slovakia was unveiled at the pre-war Košice Orthodox synagogue in 1992.[38]

Soviet occupation

[edit]The Soviet Union captured the town in January 1945, and for a short time, it became a temporary capital of the restored Czechoslovak Republic until the Red Army had reached Prague. Among other acts, the Košice Government Programme was declared on April 5, 1945.[35]

A large population of ethnic Germans in the area was expelled and sent on foot to Germany or to the Soviet border.[39]

After the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia seized power in Czechoslovakia in February 1948, the city became part of the Eastern Bloc. Several cultural institutions that still exist were founded, and large residential areas around the city were built. The construction and expansion of the East Slovak Ironworks caused the population to grow from 60,700 in 1950 to 235,000 in 1991. Before the breakup of Czechoslovakia (1993), it was the fifth-largest city in the federation.

Under Slovakia

[edit]Following the Velvet Divorce and creation of the Slovak Republic, Košice became the second-largest city in the country and became a seat of a constitutional court. Since 1995, it has been the seat of the Archdiocese of Košice.

After 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Košice, as a regional metropolitan area, became a major hub for administration, transfer and housing of refugees fleeing from Ukraine.[40][41]

Geography

[edit]Košice lies at an altitude of 206 metres (676 ft) above sea level and covers an area of 242.77 square kilometres (93.7 sq mi).[42] It is located in eastern Slovakia, about 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the Hungarian, 80 kilometres (50 mi) from the Ukrainian, and 90 kilometres (56 mi) from the Polish borders. It is about 400 kilometres (249 mi) east of Slovakia's capital Bratislava and a chain of villages connects it to Prešov which is about 36 kilometres (22 mi) to the north.

Košice is on the Hornád River in the Košice Basin, at the easternmost reaches of the Slovak Ore Mountains. More precisely, it is a subdivision of the Čierna hora mountains in the northwest and Volovské vrchy mountains in the southwest. The basin is met on the east by the Slanské vrchy mountains.

Climate

[edit]Košice has a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb, Trewartha Dcbo), as the city lies in the north temperate zone. The city has four distinct seasons with long, warm summers with cool nights and long, cold, and snowy winters. Precipitation varies little throughout the year with abundance precipitation that falls during summer and only few during winter. The coldest month is January, with an average temperature of −2.6 °C (27.3 °F), and the hottest month is July, with an average temperature of 19.3 °C (66.7 °F).

| Climate data for Košice, Slovakia (1991−2020 normals, extremes 1951−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.2 (55.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

32.0 (89.6) |

36.0 (96.8) |

38.5 (101.3) |

37.4 (99.3) |

34.1 (93.4) |

26.6 (79.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.8 (76.6) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.9 (28.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

4.5 (40.1) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

5.3 (41.5) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

5.2 (41.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.9 (−16.4) |

−22.3 (−8.1) |

−17.1 (1.2) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

−21.3 (−6.3) |

−26.9 (−16.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 25.7 (1.01) |

26.8 (1.06) |

23.6 (0.93) |

42.4 (1.67) |

69.4 (2.73) |

87.5 (3.44) |

93.5 (3.68) |

66.5 (2.62) |

50.1 (1.97) |

51.1 (2.01) |

40.2 (1.58) |

36.1 (1.42) |

613.0 (24.13) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.7 | 10.8 | 9.0 | 10.8 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 12.9 | 9.7 | 10.7 | 11.0 | 11.9 | 14.2 | 140.4 |

| Average snowy days | 14.0 | 10.9 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 4.8 | 12.7 | 50.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.5 | 78.7 | 68.4 | 61.7 | 66.0 | 66.8 | 67.0 | 66.3 | 71.6 | 78.1 | 83.5 | 86.0 | 73.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 57.0 | 83.9 | 155.5 | 200.5 | 239.9 | 253.4 | 258.9 | 264.7 | 189.4 | 131.0 | 66.7 | 41.0 | 1,941.9 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organisation[43][44] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: SHMI (extremes, 1951-present)[45] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1869 | 21,700 | — |

| 1890 | 28,900 | +33.2% |

| 1910 | 44,200 | +52.9% |

| 1921 | 52,900 | +19.7% |

| 1930 | 70,111 | +32.5% |

| 1950 | 60,700 | −13.4% |

| 1961 | 79,400 | +30.8% |

| 1970 | 149,555 | +88.4% |

| 1980 | 202,368 | +35.3% |

| 1991 | 235,160 | +16.2% |

| 2001 | 236,093 | +0.4% |

| 2011 | 240,688 | +1.9% |

| 2021 | 229,040 | −4.8% |

Košice has a population of 225,044 (2024). According to the 2021 census, 84% of inhabitants are of Slovak nationality, 2% are each Hungarians and additional 2% Roma. There are also modestly sized Czech, Ruthenian, Ukrainian and Vietnamese communities. In terms of religion, 51% of inhabitants are Catholic and 28% had no religious affiliation, with smaller Protestant denominations also present.[46][47] The median age as of 2024 is 44 years.

Historical demographics

[edit]According to the researchers the town had a German majority until the mid-16th century,[48] and by 1650, 72.5% of the population may have been Hungarians,[49] 13.2% was German, 14.3% was Slovak or of uncertain origin.[48] The Ottoman Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi mentioned that the city was inhabited by "Hungarians, Germans, Upper Hungarians" in 1661 when the city was under the suzerainty of Ottoman Empire and under Turkish control.[48] But by 1850, the Slovaks gained a plurality of 46.5%, with Hungarians reduced to 28.5% and Germans at 15.6%.[50]

The linguistic makeup of the town's population underwent historical changes that alternated between the growth of the ratio of those who claimed Hungarian and those who claimed Slovak as their language. With a population of 28,884 in 1891, just under half (49.9%) of the inhabitants of Košice declared Hungarian, then the official language, as their main means of communication, 33.6% Slovak, and 13.5% German; 72.2% were Roman Catholics, 11.4% Jews, 7.3% Lutherans, 6.7% Greek Catholics, and 4.3% Calvinists.[51] The results of that census are questioned by some historians[52] by claims that they were manipulated, to increase the percentage of the Magyars during a period of Magyarization.[50]

By the 1910 census, which is sometimes accused of being manipulated by the ruling Hungarian bureaucracy,[53] 75.4% of the 44,211 inhabitants claimed Hungarian, 14.8% Slovak, 7.2% German and 1.8% Polish.[54] The Jews were split among other groups by the 1910 census, as only the most frequently-used language, not ethnicity, was registered.[55] The population around 1910 was multidenominational and multiethnic, and the differences in the level of education mirror the stratification of society.[56] The town's linguistic balance began to shift towards Slovak after World War I by Slovakization in the newly established Czechoslovakia.[citation needed]

| Ethnic group | census 1850 | census 1880 | census 1890 | census 1900 | census 1910 | census 1921 |

| Hungarians | 28.5% | 39.8% | 49.9% | 66.3% | 75.4% | 21.2% |

| Slovaks | 46.5% | 40.9% | 33.6% | 22.9% | 14.8% | 59.7% |

| Germans | 15.6% | 16.7% | 13.5% | 8.1% | 7.2% | 4.0% |

According to the 1930 census, the city had 70,111, with 230 Gypsies (today Roma), 42 245 Czechoslovaks (today Czechs and Slovaks), 11 504 Hungarians, 3 354 Germans, 44 Poles, 14 Romanians, 801 Ruthenians, 27 Serbocroatians (today Serbs and Croatians) and 5 733 Jews.[57]

As a consequence of the First and Second Vienna Awards, Košice was ceded to Hungary. Starting in 15 May 1944, during the German occupation of Hungary towards the end of World War II, approximately 10,000 Jews were deported by the Nazis, with the enthusiastic assistance of the Hungarian Interior Ministry and its gendarmerie (the csendőrség).[58] The last transport to Auschwitz left the city in 2 June, three months before the Arrow Cross Party gained control over Hungary. The ethnic makeup of the town was dramatically changed by the persecution of the town's large Hungarian majority, population exchanges between Hungary and Slovakia and Slovakization and by mass migration of Slovaks into newly built communist-block-microdistricts, which increased the population of Košice four times by 1989 and made it the fastest growing city in Czechoslovakia.[59]

Culture

[edit]Performing arts

[edit]There are several theatres in Košice. The Košice State Theater was founded in 1945 (then under the name of the East Slovak National Theater). It consists of three ensembles: drama, opera, and ballet. Other theatres include the Marionette Theatre and the Old Town Theatre (Staromestské divadlo). The presence of Hungarian and Roma minorities makes it also host the Hungarian "Thália" theatre and the professional Roma theatre "Romathan".[60]

Košice is the home of the State Philharmonic Košice (Štátna filharmónia Košice), established in 1968 as the second professional symphonic orchestra in Slovakia. It organizes festivals such as the Košice Music Spring Festival, the International Organ Music Festival, and the Festival of Contemporary art.[61]

Museums and galleries

[edit]Some of the museums and galleries based in the city include the East Slovak Museum (Vychodoslovenské múzeum), originally established in 1872 under the name of the Upper Hungarian Museum. The Slovak Technical Museum (Slovenské technické múzeum) with a planetarium, established in 1947, is the only museum in the technical category in Slovakia that specializes in the history and traditions of science and technology.[62] The East Slovak Gallery (Východoslovenská galéria) was established in 1951 as the first regional gallery with the aim to document artistic life in present-day eastern Slovakia.[63]

European Capital of Culture

[edit]In 2008 Košice won the competition among Slovak cities to hold the prestigious title European Capital of Culture 2013. Project Interface aims at the transformation of Košice from a centre of heavy industry to a postindustrial city with creative potential and new cultural infrastructure. Project authors bring Košice a concept of the creative economy – merging of economy and industry with arts, where transformed urban space encourages development of certain fields of creative industry (design, media, architecture, music and film production, IT technologies, creative tourism). The artistic and cultural program stems from a conception of sustained maintainable activities with long-lasting effects on cultural life in Košice and its region. The main project venues are:

- Kasárne Kulturpark – 19th-century military barracks turned into new urban space with a centre of contemporary art, exhibition and concert halls and workshops for the creative industry.[64]

- Kunsthalle Košice – a 1960s disused swimming pool turned into the first Kunsthalle in Slovakia.[65]

- SPOTs – the 1970s and 1980s disused heat exchangers turned into cultural "spots" in Communist-Era-block-of-flats districts.[66]

- City park, Park Komenského and Mojzesova – revitalisation of urban spaces.

- Castle of Košice, Amfiteáter, Mansion of Krásna, Handicrafts Street – reconstruction.

- Tabačka – a 19th-century tobacco factory turned into a centre of independent culture. The Tabačka Kulturfabrik, DIG gallery, Kotolňa and several artistic residents are located in the area of the former tobacco factory.

Media

[edit]The first and the oldest international festival of local TV broadcasters (founded in 1995) – The Golden Beggar, takes place every year in June in Košice.

The oldest evening newspaper is the Košický večer. The daily paper in Košice is Korzár. Recently, the daily paper Košice:Dnes (Košice: Today) came into existence.

TV stations based in Košice: TV Naša, TV Region and public TV broadcaster RTVS Televízne štúdio Košice.

Radio stations based in Košice: Rádio Košice, Dobré rádio, Rádio Kiss, Rádio Šport, and the public broadcaster RTVS Rádio Regina Košice

Economy

[edit]

Košice is the economic hub of eastern Slovakia. It accounts for about 9% of the Slovak gross domestic product.[citation needed] The steel mill, U.S. Steel Košice with 13,500 employees, is the largest employer in the city and the largest private employer in the country.[67] The second-largest employer in the east of the country is Deutsche Telekom IT Solutions Slovakia. It was established and has been based in Košice since 2006. Deutsche Telekom IT Solutions Slovakia had 4,545 employees in Košice in Q4 of 2020, which makes it the second-largest shared service center in Slovakia and one of the top fifteen largest employers in Slovakia. As part of the growing ICT field, Košice IT Valley association was established in 2007 as a joint initiative of educational institutions, government and leading IT companies. In 2012 it was transformed into the cluster. In 2018 the cluster was for the second time certified for "Cluster Management Excellence Label GOLD" as the first in central Europe and is one of three certified clusters in the area of information and communication technologies. Volvo Cars has invested $1.2 billion euros ($1.25 billion USD) in a new plant which is set to start construction in 2023, for opening in 2026. Other major sectors include mechanical engineering, food industry, services, and trade.[68] GDP per capita in 2001 was €4,004, which was below Slovakia's average of €4,400.[68] The unemployment rate was 8.32% in November 2015, which was below the country's average 10.77% at that time.[69]

The city has a balanced budget of 224 million euros, as of 2019[update]).[70]

Sights

[edit]

The city centre, and most historical monuments, are located in or around the Main Street (Hlavná ulica) and the town has the largest number of protected historical monuments in Slovakia.[71] The most dominant historical monument of the city is Slovakia's largest church, the 14th century Gothic Cathedral of St. Elizabeth; it is the easternmost cathedral of western-style Gothic architecture in Central Europe,[71] and is the cathedral of the Archdiocese of Košice. In addition to St. Elizabeth, there is the 14th century St. Michael Chapel, the St. Urban Tower, and the Neo-baroque State Theater in the center of town.

The Executioner's Bastion and the Mill Bastion are the remains of the city's previous fortification system. The Church of the Virgin Mary's Birth is the cathedral for the Greek Catholic Eparchy of Košice. Other monuments and buildings of cultural and historical interest are; the old Town Hall, the Old University, the Captain's Palace, Liberation Square, as well as a number of galleries (the East Slovak Gallery) and museums (the East Slovak Museum). There is a Municipal Park located between the historical city centre and the main railway station. The city also has a zoo located northwest of the city, within the borough of Kavečany.

Places of worship

[edit]Government

[edit]

Košice is the seat of the Košice Region, and since 2002 it is the seat of the autonomous Košice Self-governing Region. Additionally, it is the seat of the Slovak Constitutional Court. The city hosts a regional branch of the National Bank of Slovakia (Národná banka Slovenska) and consulates of Belgium, Greece, Hungary, Russia, Spain and Turkey.

The local government is composed of a mayor (Slovak: primátor), a city council (mestské zastupiteľstvo), a city board (mestská rada), city commissions (Komisie mestského zastupiteľstva), and a city magistrate's office (magistrát). The directly elected mayor is the head and chief executive of the city. The term of office is four years. The previous mayor, František Knapík, was nominated in 2006 by a coalition of four political parties KDH, SMK, and SDKÚ-DS. In 2010 he finished his term of office.[72] The present mayor is Ing. Jaroslav Polaček. He was inaugurated on 10 December 2018.[73]

In 2021, the municipality recycled 24.64% of its municipal waste.[74]

Administratively, the city of Košice is divided into four districts: Košice I (covering the center and northern parts), Košice II (covering the southwest), Košice III (east), and Košice IV (south) and further into 22 boroughs (wards):

| District | Boroughs |

|---|---|

| Košice I | Džungľa, Kavečany, Sever, Sídlisko Ťahanovce, Staré Mesto, Ťahanovce |

| Košice II | Lorinčík, Luník IX, Myslava, Pereš, Poľov, Sídlisko KVP, Šaca, Západ |

| Košice III | Dargovských hrdinov, Košická Nová Ves |

| Košice IV | Barca, Juh, Krásna, Nad jazerom, Šebastovce, Vyšné Opátske |

Education

[edit]Košice is the second university town in Slovakia, after Bratislava. The Technical University of Košice is its largest university, with 16,015 students, including 867 doctoral students.[75] A second major university is the Pavol Jozef Šafárik University, with 7,403 students, including 527 doctoral students.[76] Other universities and colleges include the University of Veterinary Medicine in Košice (1,381 students)[77] and the private Security Management College in Košice (1,168 students).[78] Additionally, the University of Economics in Bratislava, the Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, and the Catholic University in Ružomberok each have a branch based in the city.

There are 38 public elementary schools, six private elementary schools, three religious elementary schools, and one International Baccalaureate (IB) Primary Years Programme (PYP) candidate international school.[79] Overall, they enroll 20,158 pupils.[79] The city's system of secondary education (some middle schools and all high schools) consists of 20 gymnasia with 7,692 students,[80] 24 specialized high schools with 8,812 students,[81] and 13 vocational schools with 6,616 students.[82][83]

Kosice International School (KEIS) is the first international primary school in Eastern Slovakia. It will be an International Baccalaureate (IB) Primary Years Programme (PYP) international school. Opening in September 2020.[84]

Notable personalities

[edit]Transport

[edit]

Public transport in Košice is managed by Dopravný podnik mesta Košice[85] ("Public Transport Company of the City of Košice"). The municipal mass transit system is the oldest one in present-day Slovakia, with the first horse-car line beginning operation in 1891 (electrified in 1914).[33] Today, the city's public transportation system is composed of buses (in use since the 1950s), trams, and trolleybuses (since 1993).

Košice railway station is a rail hub of eastern Slovakia. The city is connected by rail to Prague, Bratislava, Prešov, Čierna nad Tisou, Humenné, Miskolc (Hungary), and Zvolen. There is a broad gauge track from Ukraine, leading to the steel mill southwest of the city. The D1 motorway connects the city to Prešov, and more motorways and roads are planned around the city.[86]

Košice International Airport is located south of the city. Regular direct flights from the airport are available to London Luton and Stansted (from April 2020), Vienna, Warsaw, Düsseldorf and Prague.[87] Regular flights are provided by Czech Airlines, Austrian Airlines, Eurowings, LOT Polish Airlines and Wizz Air and in code-share by Air France-KLM and Lufthansa. At its peak in the year 2008, it served 590,919 passengers, but the number has since declined.[88]

Sports

[edit]

The Košice Peace Marathon (founded in 1924) is the oldest annual marathon in Europe and the third oldest in the entire world, after the Boston Marathon and the Yonkers Marathon. It is run in the historic part of the city and is organized every year on the first Sunday of October.

Ice hockey club HC Košice is one of the most successful Slovak hockey clubs. It plays in Slovakia's highest league, the Extraliga, and has won eight titles in 1995, 1996, 1999, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2014, and 2015; and two titles (1986 and 1988) in the former Czechoslovak Extraliga. Since 2006, their home is the Steel Aréna which has a capacity of 8,343 spectators. Košice was once home to football club MFK Košice until it folded due to bankruptcy. It was the first club from Slovakia reach the group stages of the UEFA Champions League and won the domestic league twice (1998 and 1999). Another football club, FC VSS Košice last played in the 2. Liga in the 2016-17 season, with a new home stadium known as the Košická futbalová Arena (KFA). It merged with FK Košice-Barca in 2018 to become FC Košice.

Košice, along with Bratislava hosted the 2011 and 2019 IIHF World Championship in ice hockey.

Košice became the 2016 European City of Sport[89] by the European Capitals of Sports Association (ACES Europe). The sporting events in 2016 included "the International Peace Marathon, several urban runs, a swimming relay contest, the Košice-Tatry- Košice cycling race, the dancesport world championships, the Basketball Euroleague, Volleyball World League and Water Polo World League".[90]

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]

Abaújszántó, Hungary (2007)

Abaújszántó, Hungary (2007) Budapest, Hungary (1997)

Budapest, Hungary (1997) Bursa, Turkey (2000)

Bursa, Turkey (2000) Cottbus, Germany (1992)

Cottbus, Germany (1992) Da Nang, Vietnam (2015)

Da Nang, Vietnam (2015) Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (2016)

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (2016) Katowice, Poland (1991)

Katowice, Poland (1991) Krosno, Poland (1991)

Krosno, Poland (1991) Miskolc, Hungary (1997)

Miskolc, Hungary (1997) Mobile, United States (2000)

Mobile, United States (2000) Niš, Serbia (2000)

Niš, Serbia (2000) Ostrava, Czech Republic (2001)

Ostrava, Czech Republic (2001) Plovdiv, Bulgaria (2000)

Plovdiv, Bulgaria (2000) Raahe, Finland (1987)

Raahe, Finland (1987) Rzeszów, Poland (1991)

Rzeszów, Poland (1991) Uzhhorod, Ukraine (1993)

Uzhhorod, Ukraine (1993) Vysoké Tatry, Slovakia (2006)

Vysoké Tatry, Slovakia (2006) Wuhan, China (2012)

Wuhan, China (2012) Wuppertal, Germany (1980)

Wuppertal, Germany (1980)

Former twin cities

[edit]As a result of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine the City Council had terminated cooperation with the following cities:[92]

Vitebsk, Belarus (2015)

Vitebsk, Belarus (2015) Saint Petersburg, Russia (1995)

Saint Petersburg, Russia (1995)

See also

[edit]- Košice Peace Marathon

- List of people from Košice

- List of municipalities and towns in Slovakia

- Zlaty dukat

Notes

[edit]- ^ German: Kaschau [ˈkaʃaʊ] ⓘ; Polish: Коszyce [kɔˈʂɨt͡sɛ]; Rusyn and Russian: Кошице, romanized: Koshitse [ˈkoʂɨtsɨ]; Ukrainian: Кошиці, romanized: Koshytsi [ˈkɔʃɪts⁽ʲ⁾i].

References

[edit]- ^ Združenie Feman (2009). "Feman – Európsky festival kultúry národov a národností".

- ^ "Obyvatelia - Infopanel Krajské mestá SR". krajskemesta.statistics.sk. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ "Košice". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.[dead link]

- ^ Lucinda Mallows: Slovakia: The Bradt Travel Guide, Globe Pequot Press, Connecticut, 2007

- ^ a b City of Košice (2005). "Short History of Košice". Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ "Z histórie Košíc – 13. storočie" (in Slovak). City of Košice. 2005. Archived from the original on June 27, 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Štefánik, Martin; Lukačka, Ján, eds. (2010). Lexikón stredovekých miest na Slovensku [Lexicon of Medieval Towns in Slovakia] (PDF) (in Slovak and English). Bratislava: Historický ústav SAV. p. 194. ISBN 978-80-89396-11-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 2, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ Varsik, Branislav (1964). Osídlenie Košickej kotliny I. (in Slovak). Bratislava: Veda, Vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied. p. 193. ISBN 978-80-89396-11-5.

- ^ Room, Adrian (December 31, 2003). Placenames of the world: origins and... – Google Books. ISBN 9780786418145. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Old Hungarian names" (PDF). 2009.

- ^ Magyar Nyelvtudományi Társaság (Society of Hungarian Linguistics), Magyar nyelv, Volume 18, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1922, p. 142, Cited: "Kokos (Kakas), Kolumbán (Kálmán), Kopov (Kopó), Kokot (Kakat hn.) stb. Bármely ilyen Ko- szótagon kezdődő tulajdonnévnek lehet a Kosa a származéka. E Kosa szn. van nézetünk szerint Kassa (régen Kossa -=: Kosa) város nevében is/Kokos (Kakas), Kolumbán (Kálmán), Kopov (Kopó), Kokot (Kakat hn.) etc., any proper nouns that begin with 'Ko' syllable may have Kosa derivative, in the name of Kassa as well (its old form Kossa, Kosa)"

- ^ Vlastivedný Slovník Obcí na Slovensku, VEDA, vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied, Bratislava 1978.

- ^ Milan Majtán (1998), Názvy Obcí Slovenskej republiky (Vývin v rokoch 1773–1997), VEDA, vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied, Bratislava, ISBN 80-224-0530-2.

- ^ Lelkes György (1992), Mayar Helységnév-Azonosító Szótár, Balassi Kiadó, Budapest, ISBN 963-7873-00-7.

- ^ a b Papp, Sándor. "Slovakya'nın Tarihi". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. 33: 337. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ^ a b "Zaujímave letopočty z dejín mesta Košice – 1143–1560" (in Slovak). City of Košice. 2005. Archived from the original on May 10, 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ "Z histórie Košíc – 14. storočie" (in Slovak). City of Košice. 2005. Archived from the original on June 25, 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ Rady, Martyn C. (2000). Nobility, land and service in medieval Hungary. University of London. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-333-80085-0.

- ^ "Warfare in Fourteenth Century Hungary, from the Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum". De Re Militari, an international scholarly association. Archived from the original on September 17, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ Matica slovenská, Kniha, Matica slovenská, 2008, p. 16

- ^ R.O.Halaga: Právny, územný a populačný vývoj mesta Košíc, Košice 1967, p.54

- ^ "Pallas Nagy Lexikona" (in Hungarian). City of Kassa. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ Mahoney, William (February 18, 2011). The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313363061 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Hötte, Hans H. A. (December 17, 2014). Atlas of Southeast Europe: Geopolitics and History. Volume One: 1521–1699. BRILL. ISBN 9789004288881 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Tenderlap" (in Hungarian). City of Košice. Archived from the original on July 7, 2007.

- ^ a.s., Petit Press. "HISTÓRIA".

- ^ "The Treaty of Vasvár: What Was Lost, and What Remained". mek.oszk.hu.

- ^ "A történeti Magyarország katolikus levéltárai / Eger" (in Hungarian). City of Košice. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009.

- ^ "Z histórie Košíc – 18. storočie" (in Slovak). City of Košice. n.d. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Immaculata". City of Košice. 2005. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ "Kazinczy Ferenc" (in Hungarian). City of Košice. Archived from the original on February 19, 2009.

- ^ "MEK (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár)" (in Hungarian). City of Košice.

- ^ a b c "Zaujímave letopočty z dejín mesta Košice (1657–1938)" (in Slovak). City of Košice. n.d. Archived from the original on May 15, 2007. Retrieved January 20, 2008.

- ^ "Rákóczi in Košice 1906–2006 – Who was Francis II Rákóczi?". various. February 24, 2006. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ^ a b "Z histórie Košíc – 20. storočie (Slovak)" (in Slovak). City of Košice. 2005. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2008.

- ^ Dreisziger, Nándor F. (1972). "New Twist to an Old Riddle: The Bombing of Kassa (Košice), June 26, 1941". Journal of Modern History. 44 (2): 232–42. doi:10.1086/240751. S2CID 143124708.

- ^ "ארכיון בית העדות - תוצאות חיפוש". www.catalog-beit-haedut.org.il.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Memorial plaque in the synagogue of Košice". Holocaust Memorials: Monuments, Museums and Institutions in Commemoration of Nazi Victims. Berlin, Germany: Stiftung Topographie des Terrors. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Forgotten Voices page 97

- ^ a.s, Petit Press (March 1, 2022). "Station in Košice full of refugees, mostly students from Africa". spectator.sme.sk. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Florkiewicz, Pawel; Komuves, Anita (February 26, 2022). "Refugees flee Ukraine across EU borders as Russia renews assault". Reuters. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ "Municipal Statistics". Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Košice". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on August 7, 2023. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ "Kosice Airport Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 7, 2023. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ "Košice Barca" (in Italian). Slovak Hydrometeorological Institute. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ "Údaje o obyvateľoch" (PDF). Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "Základná charakteristika - demografické údaje :: Oficiálne stránky mesta Košice". www.kosice.sk (in Slovak). Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c Károly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi, Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, Simon Publications LLC, 1998, p. 46-47 [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ Kocsis, Karoly; Kocsis-Hodosi, Eszter (April 1, 2001). Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin. Simon Publications, Incorporated. ISBN 9781931313759 – via Google Books.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b HOLEC, Roman. Trianon rituals or considerations of some features of Hungarian historiography. Historický časopis, 2010, 58, 2, pp. 291-312, Bratislava.

- ^ "A Pallas nagy lexikona; Az összes ismeretek enciklopédiája". X, Kacs−Közellátás (1 ed.). Budapest: Pallas Irodalmi és Nyomdai Részvénytársaság. 1895.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Murad, Anatol (1968). Franz Joseph I of Austria and His Empire – Google Knihy. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Teich, Mikuláš; Dušan Kováč; Martin D. Brown (2011). Slovakia in History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139494946. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ Atlas and Gazetteer of Historic Hungary 1914, Talma Kiadó Archived January 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Abaúj-Torna County". Retrieved January 26, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Karády, Viktor; Nagy, Péter Tibor (January 10, 2006). Educational inequalities and denominations, 1910 : Vol. 2. Database for Eastern-Slovakia and North-Eastern Hungary. In the course of research : Sociology of religion. J. Wesley Publ. ISBN 9789638718198.

- ^ Encyklopedie branné moci Republiky Československé. 2006 J. Fidler, V. Sluka

- ^ "Židia v Košiciach" (in Slovak). Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ^ KOROTNOKY, Ľudovít (ed.). Košice : sprievodca. Košice : Východoslovenské tlačiarne, 1989. 166 s. ISBN 80-85174-40-5.

- ^ "Košice – metropola východného Slovenska" (in Slovak). Košice.info. 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ "The Slovak State Philharmonic, Košice – History". The Slovak State Philharmonic, Košice. n.d. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009.

- ^ "Slovenské technické múzeum – História múzea" (in Slovak). n.d. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ "Východoslovenská galéria" (in Slovak). cassovia.sk. n.d. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ "Kasárne Kulturpark", Wikipédia (in Slovak), April 29, 2022, retrieved June 12, 2022

- ^ "Kunsthalle Košice", Wikipédia (in Slovak), February 5, 2021, retrieved June 12, 2022

- ^ s.r.o, Adsulting. "EN". Výmenníky (in Slovak). Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Urban Audit". Archived from the original on November 9, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ^ "Nezamestnanosť – mesačné štatistiky" (in Slovak). Central Office of Labour, Social Affairs and Family. 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ "Uznesenie z II. rokovania Mestského zastupiteľstva v Košiciach, zo dňa 22. februára 2007" (RTF) (in Slovak). City of Košice. 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ a b "Town monument reserve – Košice". Slovak Tourist Board. 2007. Archived from the original on October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ "František Knapík". Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a.s, Petit Press. "Nový košický primátor sľúbil návrat trolejbusov aj protikorupčný audit". kosice.korzar.sme.sk (in Slovak). Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ "Komunálny odpad :: Oficiálne stránky mesta Košice". www.kosice.sk (in Slovak). Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "Technická univerzita Košice" (PDF) (in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ "Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika" (PDF) (in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ "Univerzita veterinárneho lekárstva" (PDF) (in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Retrieved February 14, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Vysoká škola bezpečnostného manažérstva" (PDF) (in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ a b "Prehľad základných škôl v školskom roku 2006/2007" (PDF) (in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ "Prehľad gymnázií v školskom roku 2006/2007" (PDF) (in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ "Prehľad stredných odborných škôl v školskom roku 2006/2007" (PDF) (in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ "Prehľad združených stredných škôl v školskom roku 2006/2007" (PDF) (in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ "Prehľad stredných odborných učilíšť a učilíšť v školskom roku 2006/2007" (PDF) (in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ "Kosice International School" (in English and Slovak). KEIS. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ "Dopravný podnik mesta Košice, a.s. – DPMK". www.dpmk.sk.

- ^ Ján Gana (2007). "Highways and tunnels in Slovakia". Archived from the original on February 1, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ "Košice International Airport – Departures". Košice International Airport. 2010. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "Košice International Airport – Statistics". Košice International Airport. 2010. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "EMS Košice - PZP". EMS Košice.

- ^ "Kosice 2016 International City of Sport". Kosice International Airtport. bart.sk. 2012.

- ^ "Twin cities of the City of Košice". Košice. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "Tlačová agentúra Slovenskej republiky - TASR.sk". www.tasr.sk. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dreisziger, Nándor F. (1972). "New Twist to an Old Riddle: The Bombing of Kassa (Košice), June 26, 1941". Journal of Modern History. 44 (2): 232–42. doi:10.1086/240751. S2CID 143124708.

- Kinselbaum, Stanislav J. (2006). The A to Z of Slovakia. A to Z Guide Series, 236. Toronto, Canada: The Scarecrow Press.

External links

[edit]Official sites

[edit] Media related to Košice at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Košice at Wikimedia Commons- Official website of the town of Košice

- Official Tourism and Travel Guide to Košice

- DPMK – Public Transport Office Site

Tourism and living information

[edit] Košice travel guide from Wikivoyage

Košice travel guide from Wikivoyage- Tourist guide

- Cassovia Digitalis The Digital City Library (German/Slovak/Hungarian/English)

- Košice at funiq.eu